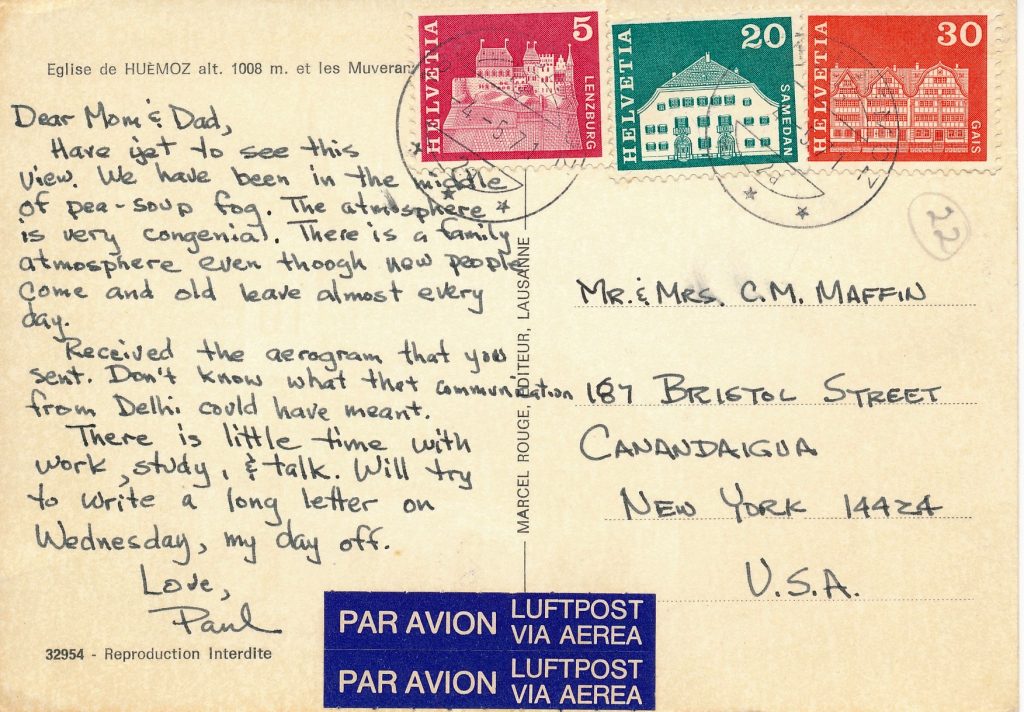

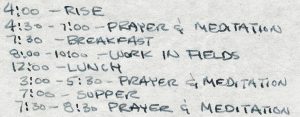

As May 1971 drew to a close, I was not sure that I would be able to stay on at L’Abri, since so many were clamoring to study at this unique place. To my surprise, Udo and Debbie along with others persuaded me to stay another month. I wrote my parents, “They must really want me and feel it’s for my good, since many others are being turned away daily. Debbie and I have had some great talks. Growing up in an environment like this has really made her extremely sensitive to all kinds of people.” I wrote to friends, “It becomes less and less easy to interpret the things I’ve gone through as anything other than the leadings of a loving God.”

Though I was still a couple months away from placing my faith fully in Jesus Christ, the simple message that I was hearing was beginning to resonate with me. There is a God who is there. Jesus Christ came in the flesh, died and rose again in space, time and history. It was dawning on me that, much more than being merely a nice concept, Christianity is a complete philosophical system, which can give strong answers to modern’s questions about self and the world. Schaeffer criticized most modern evangelism as being “contentless.” He saw modern theology’s attempts to take the Bible less and less literally in an attempt to make it more universal, as removing the great strength that it has as it stands.

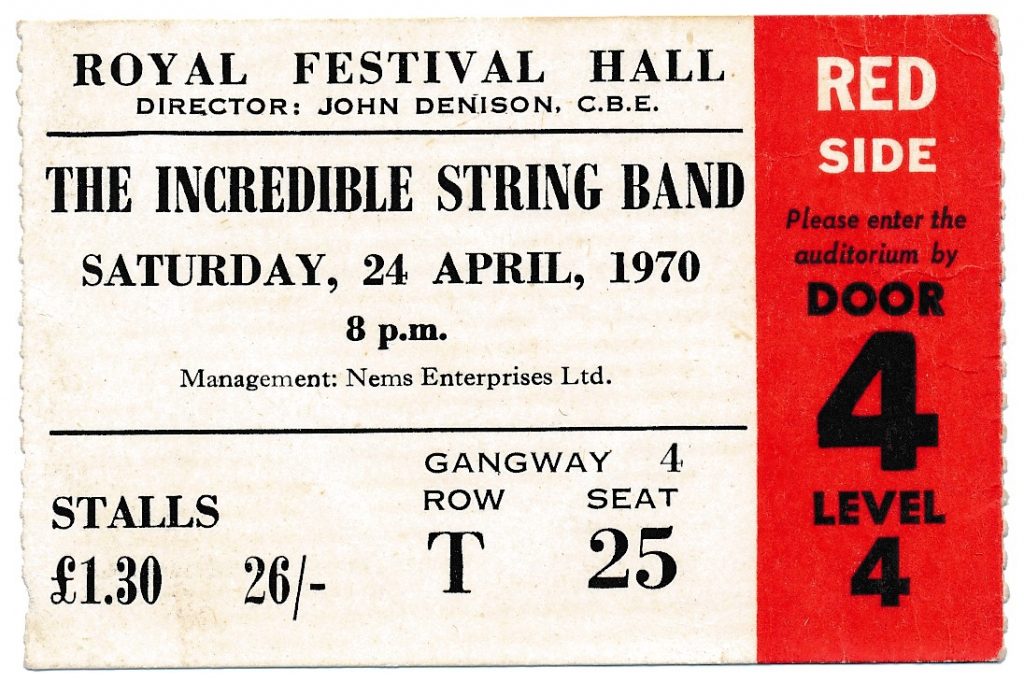

The community of L’Abri was full of music. There were several talented musicians among the workers, including the flamboyant Jane Stuart Smith, who traded a promising career in opera to join the Schaeffers in ministry at L’Abri. The chapel at L’Abri had a lovely organ built by the world-renowned organ builder, D. A. Flentrop, which was given as a gift to L’Abri by Jane’s family. I had carried a recorder (the instrument) with me throughout my travels. I was delighted to be part of a number of impromptu recorder ensembles.

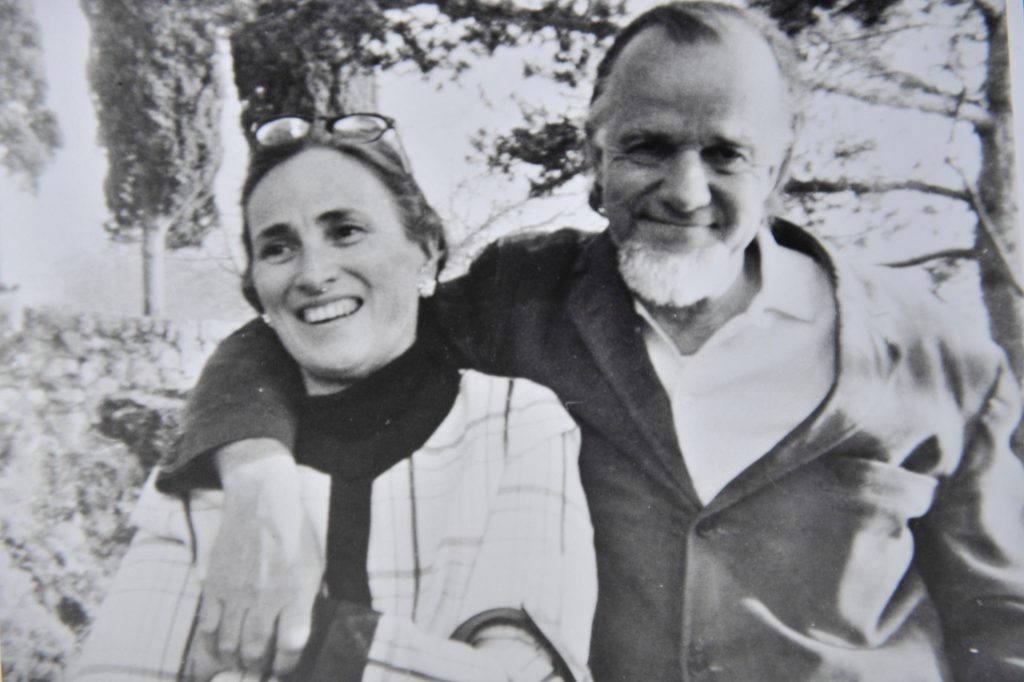

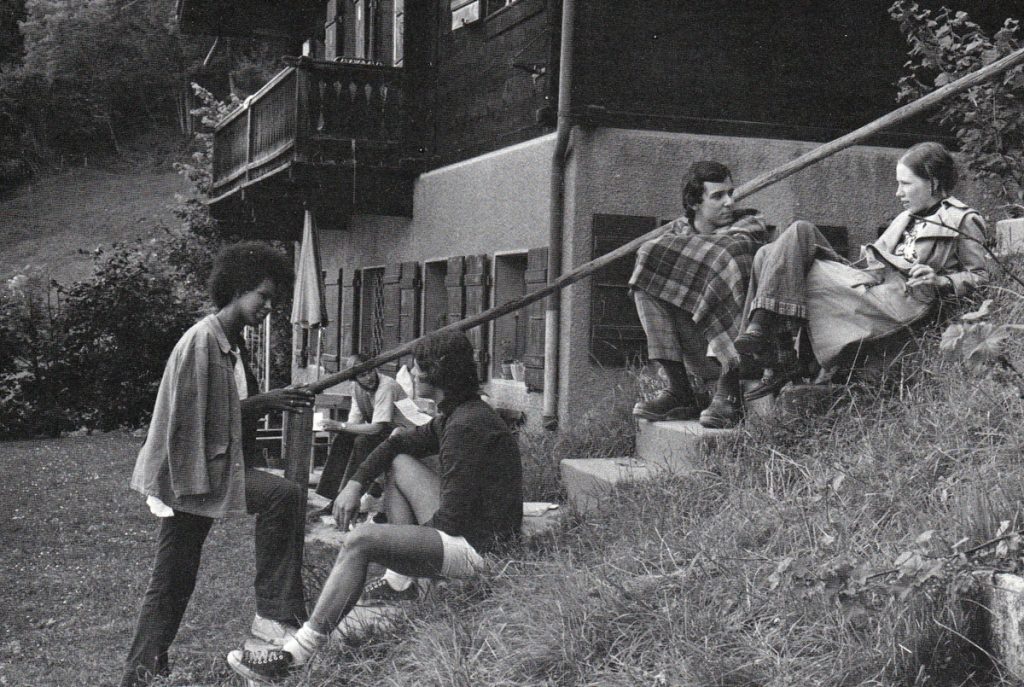

During this period, in addition to the workers of L’Abri, I received much help from people my own age who had been heavily into drugs and, like me, had spent extensive time in the East. I saw in them a real, living faith, which was beginning to fulfill their personalities. The way the schedule was structured, there was plenty of open time for interaction. The USA had just come through some times of extreme racial tensions, including the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. The blacks who came to L’Abri (and others from diverse backgrounds) found a community that was fully accepting of them.

There was an amazing guy named Mark who was staying at an extension of L’Abri in France. He was part of a group that came over to the Swiss L’Abri once a week for fellowship and to participate in a lecture. Mark and I had some great “raps.” He did acid (LSD) for about four years, and started out for Switzerland with a stock of drugs and a library of books on Eastern mysticism, planning to sit on the top of a mountain and “get his head together.”

God had other plans. His luggage was lost on the flight over. Someone he knew was at L’Abri, so he came there. Mark wrote letters to his friends about Christ illustrated with wild cartoons. He said something beautiful one time he was over for a visit. He said that he was sleeping out one night and woke under the canopy of stars and the moon glowing electrically. He said that he was just devastated by the fact that the same “cat” that made all of that also came to this smallest place to die for the sin of the world.

I was grateful for the privilege of being able to stay at L’Abri through the month of June. I really needed that time to process all of the amazing input that I was receiving, both formally and informally.