Deeper into Zen

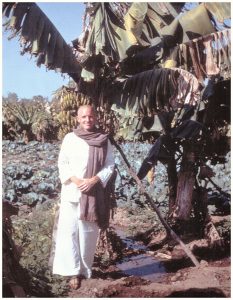

Heading into February, 50 years ago, the daily routine at the Samavaya Ashram became more natural for me. I mentioned in my previous post that part of the day was spent in work that benefitted the community. I wrote home, “The fields are beautiful. The ashram grows all of its own food and uses excellent scientific farming methods. There is wheat, rice, sugar cane, bananas, cauliflower, eggplant, and much more. Lately, we have been clearing banana trees that have ceased to produce and dragging them to the compost pile. We also take turns grinding the wheat for flour [with a hand mill].” The picture below is of me standing in the farm.

I promised more detail about our times of meditation. Each of the long periods of meditation contained two 30 minute intervals of sitting mediation (zazen), a short period of walking, then a lecture and Q&A by Zengo. That meant a normal day would contain three hours of absolutely quiet and motionless meditation. Some time during each day, there was a personal interview with Zengo for each person. Here’s a sample interaction: BOW. EYES MEET. BOTH SMILE. SMILES FADE. Zengo: “What is ego?” Ego (me, giving the stock answer): “Clinging.” Zengo: “What is non-ego?” I search my mind. Ego (me, not having a clue): “I don’t know.” BOW.

Here are more thoughts that I wrote to friends, showing my thought process at the time. “The way to freedom is to have no likes or dislikes. The wash in the cold mountain stream is as beautiful as the hot tub bath. The mouthful of brown rice is as beautiful as the hot fudge sundae. The sweaty feeling at the end of work is as beautiful as the fine, cool feel after the shower 10 minutes later. As one of the people here wrote to his sister, ‘You can either do what you like or like what you do.'”

These thoughts were practical expressions of the Buddhist philosophy that all of life is impermanent, that nothing in this world lasts forever. Suffering comes from attachment, clinging to this impermanent life. Buddhists often give this illustration of the power of desire. At one time, there was a simple method used to trap monkeys. A large gourd was hollowed out with a hole just large enough for a monkey’s paw. Some treat was placed inside the gourd. The monkey was not able to pull its clenched paw out of the hole because it had the treat clenched in its paw. The monkey became trapped—not by any physical restraint but by his desire to have what was grasped in his paw. In the same way our desires trap us.

In like manner, when we learn to sever that attachment to our desires, we can be free of the mental trap which binds us to this world. This, Buddhism claims, frees us from suffering. This state of non-attachment is called by various names—Enlightenment, Satori (Japanese), Nirvana (Sanskrit). Zen further claims to offer a fast track method to reach this goal. Zen has it’s own set of scriptures, most particularly the Platform Sutra, also known as the Sutra of Huineng,

During my personal times, I was continuing to read the Bible I carried with me, not willing to totally abandon the Christian tradition of my youth. I continued to also read books that others in the group had found insightful and that they loaned to me, such as Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics by R. H. Blyth.

I will try to give a fuller sense of my journey deeper into Zen in future posts.