During the month of February 50 years ago, I began to settle into the new way of life at the Ashram. The daily rhythm of work and meditation began to feel more and more natural to me. The temperatures were still moderate with days in the 70s and nights down to the 40s. So there was little difficulty staying awake during the early morning meditation at 4:30. We usually walked once around the Mahabodhi Temple each morning at about 5:30 for a break in meditation. Most mornings we encountered an ancient Tibetan woman walking, chanting, and turning her prayer wheel. There was a prayer written around the circumference of the wheel. Each spin of the wheel supposedly repeated the prayer, thus adding to a person’s merit.

To help my parents understand the basis of Zen, I wrote this: “Most people view Zen Buddhism as highly esoteric. The basis, however, is quite simple. Ego is at the root of all evil. As long as I have a preconceived idea of what you are like, I can never see you as you really are. My love for you will never be free of self-interest. It is the same with anything—if you look at a rose and think “rose,” you start to limit it (sorry, that is a little too subtle). It’s a real difficulty to put words to things I’ve just felt for the first time.”

“Zen Buddhism teaches that people develop myriad preconceived ideas of the world and gradually become blind to things as they really are. So, when we sit for meditation, we try to quiet the mind and rid it of stray thoughts. When you observe this closely, it’s amazing to see what percentage of your thought is useful and what part is serving no purpose whatsoever. The second thrust of Zen is mindfulness. If working in the fields, have your entire attention there. Our meals are passed in silence—just eat, nothing else.”

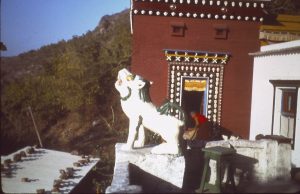

One day our meditation group took a beautiful field trip to some nearby mountains. We took horse cart about four miles. From this point we crossed the river and had about a two-mile walk along the dikes between rice paddies, wheat fields, and fields of dal (a kind of lentil). The mountain we climbed was serpent-shaped and rose abruptly out of the otherwise flat terrain. Half way up we rested and had lunch near a small Tibetan temple, which was built near a cave where Buddha practiced asceticism before coming to Bodh Gaya. The view from the top, looking on a cluster of houses, was like that from an airplane.

Although our diet remained largely the same, changing seasons brought some variety. During the month of February, we began to have some nice salads with carrot, banana and papaya. We also had a special breakfast treat from time to time called sattu, which is made from a flour ground from toasted corn, wheat and chick peas then served with sugar and hot water. It may not sound that appealing, but it was a great change of pace.

Along with my other reading, I was immersed in a couple books by Francis and Edith Shaeffer that the Stringhams loaned to me. L’Abri (the shelter) by Edith spoke about how the couple founded a Christian community in the Swiss Alps to which hundreds of people (both Christians and seekers) come from all over the world to study and be part of a community seeking to live out their faith. The God Who Is There by Francis interacts with the main philosophical currents of Western thought from a Christian perspective. I was intrigued by what I was reading.

At the end of February, I took off for New Delhi to check for mail and update my visa then took my favorite overnight 3rd class sleeper to Lucknow to spend a few days with the Stringhams before returning to Bodh Gaya to continue my meditation practice.