Sarnath and Christmas

At this point in my travels, I was becoming disillusioned with what I observed of how the Hindu worldview worked out in everyday life. In an earlier post, I mentioned the cows that wandered about everywhere in the cities of India. Cows are regarded as sacred by most Hindus. In fact, I observed that cows were often treated better than humans. The idea that all life is sacred sounds exalted and noble. The reality is that if all life is sacred, then there is nothing really special about human life.

I also saw the outworking of the caste system, which was officially abolished in 1950 but which did (and still does) exercise great power in India. Those at the bottom of the hierarchy, who fall outside the four main categories of Brahmins (priests and teachers), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (traders and merchants) and the Shudras (laborers), are considered “untouchables” or Dalits. This whole system of caste is tied to Hinduism and the concept of karma and reincarnation. That view says that, when I die, if I have lived a virtuous life, I will be reborn into better life circumstances. If I have led a bad life, then I will be reborn into worse life circumstances. The inescapable conclusion is that those of lower caste deserve to be there because of evil done in a previous life.

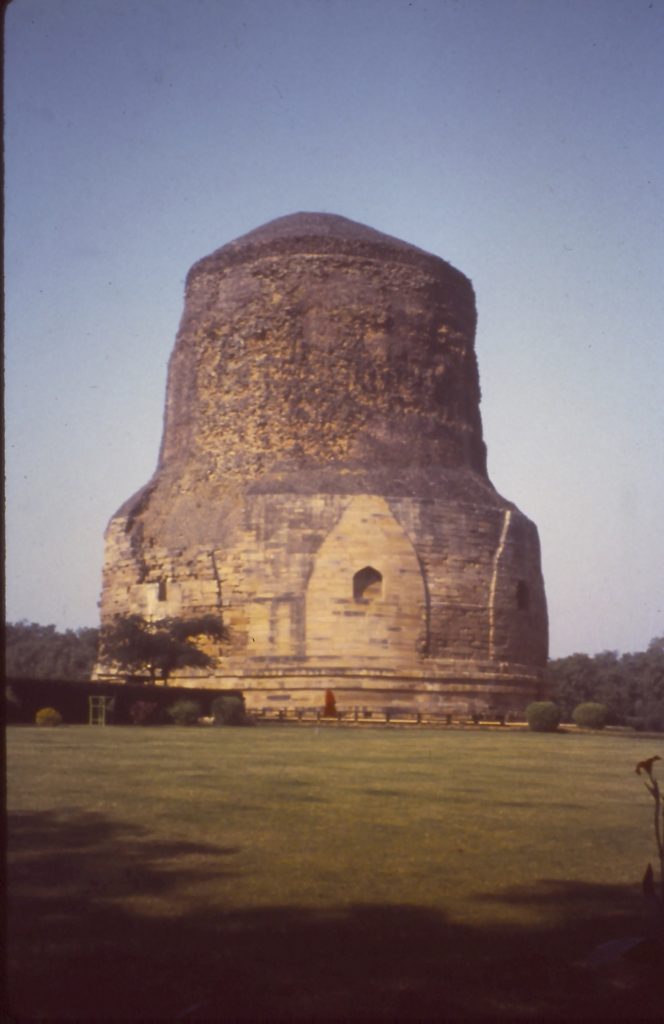

Even though Buddhism holds to the same philosophy of karma and reincarnation, it didn’t seem to me at the time to have the same disastrous social consequences. As a result I channeled my hunger for truth toward Buddhism for the remainder of my time in India. The first deliberate step in that direction was traveling from Benares to Sarnath, about seven miles distant. This village is sacred to Buddhists because it is where Gautama Buddha supposedly preached his first sermon. It was a peaceful village with a large Buddhist monument or stupa, which dates from the 6th century and sits atop an older structure built by King Asoka in 249 BC. If you look closely at my photo, you can see a red robed Tibetan Buddhist monk walking around the stupa.

There was a dharamshala (a rest house for spiritual pilgrims) in Sarnath, where those who stay pay what they can afford. I was able to stay for a few days and planned to return for a longer stay in the New Year (1971). While in Sarnath, I met an Indian doctor who was an instructor in preventive medicine, running free clinics in neighboring villages. He was reading “Politics of Ecstasy” (by Timothy Leary) and had turned on once to LSD.

I was reading voraciously and widely at the time. While there I read Aldous Huxley’s Island and Beyond the Tenth by a man born Cyril Henry Hoskin who claimed that his body hosted the spirit of a Tibetian lama by the name of T. Lobsang Rampa. I was also starting to build a small library of some of the Buddhist classics, such as the Diamond Sutra and The Dhammapada, which gave me a solid foundation for understanding classical Buddhist thought.

The Stringhams had invited me to spend time with them at Christmas, so I headed back to Lucknow a couple days before Christmas. I truly enjoyed being with a family for Christmas and relished the church services with many of the traditional Christmas carols. Even though I was becoming more drawn to Buddhism, I still considered myself a Christian and believed there was a legitimate way to blend an Eastern worldview with the Christian faith. Would a true synthesis really be possible?