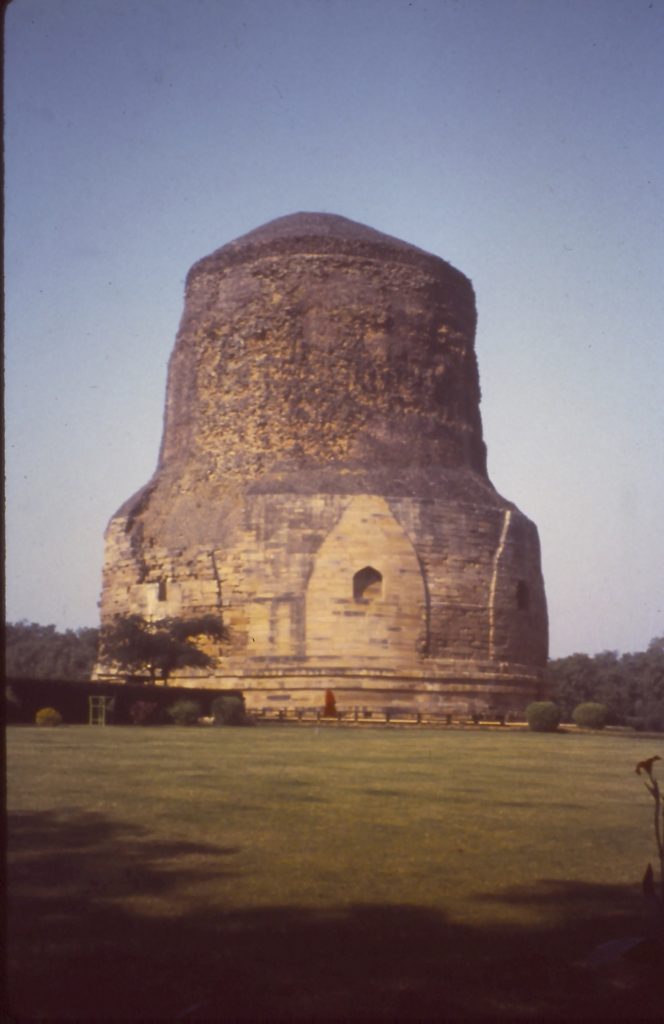

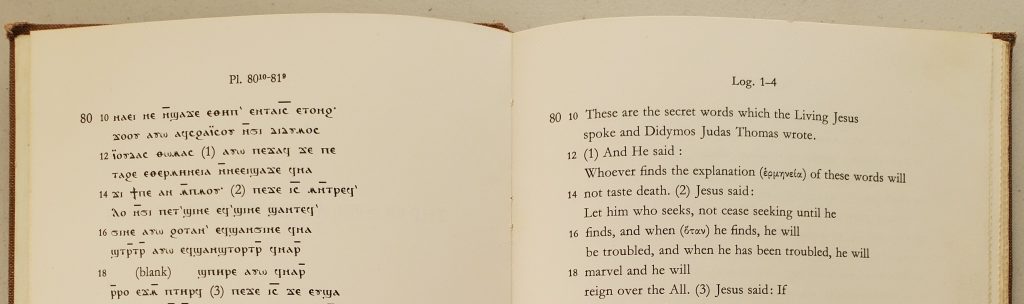

After my time with Jonathan and family, I headed back to Sarnath, the village outside of Benares that I had found so attractive. My plan was to stay for a month of R&R—reading and rumination. I was reading a wide variety of books at the time. In addition to the Bible that I brought with me, I also had a copy of The Gospel According to Thomas, a Coptic text discovered in 1945 and claiming to be “the hidden words which the Living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas wrote.” This so-called gospel appealed to me then and continues to appeal to many today because it presents mystical sayings claiming to come from Jesus, which are much easier to integrate with Eastern teachings than any of Jesus’ authentic teaching contained in the Gospels in the Bible—Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Along with the Buddhist texts that I mentioned in an earlier posts, I was reading things like The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise by R. D. Lang, a Scottish psychiatrist. I reread some of Aldous Huxley’s works. You can hear in these words written to friends that I was being drawn to look deeper within myself for some stable point in the ever changing world. “Each day the world goes on to a different state than that in which we saw it the day before. If we are not equipped with new vision for that day—that is if we rely on yesterday’s insights—we begin to fall behind and in the end understand very little.”

I wrote this to my parents about my time in Sarnath: “As with most places I have stayed in India, my accommodation is a small room with bed, desk and chair. The floor is concrete and the walls and ceiling are whitewashed. Here are both Indians and Tibetans. So, for one meal I have rice, vegetable curry, dal (like lentils), and chapati (flat, unleavened wheat bread). For the other I have thukpa (Tibetan noodle soup) and momo (meat wrapped in dough and cooked in steam—like wanton).”

My plans to stay for a month in Sarnath were cut short abruptly. The dharmsala where I was staying was becoming crowded, and pilgrims had first preference, so I was required to leave. Several people had told me about the beauty of a small village called Bodh Gaya, the place where Gautama Buddha received his Enlightenment. There are numerous temples in the town built by nearly every Buddhist nation. At first it appeared that I was again out of luck, since most lodging places were full because of a ten-day meditation course being offered at the Burmese monastery.

I was about to leave when someone suggested an ashram hidden back from the main street and just across from the Mahabodhi temple, the central Buddhist temple in Bodh Gaya (see my picture above). So it was that I arrived at the Samanvaya Ashram, which was founded by Vinoba Bhave, a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi, as a center for work and for promoting the founder’s understanding that the religions of the world have a common basis. At the time I arrived, a special program had just begun—mainly for the Westerners here. Much more about that in future posts.